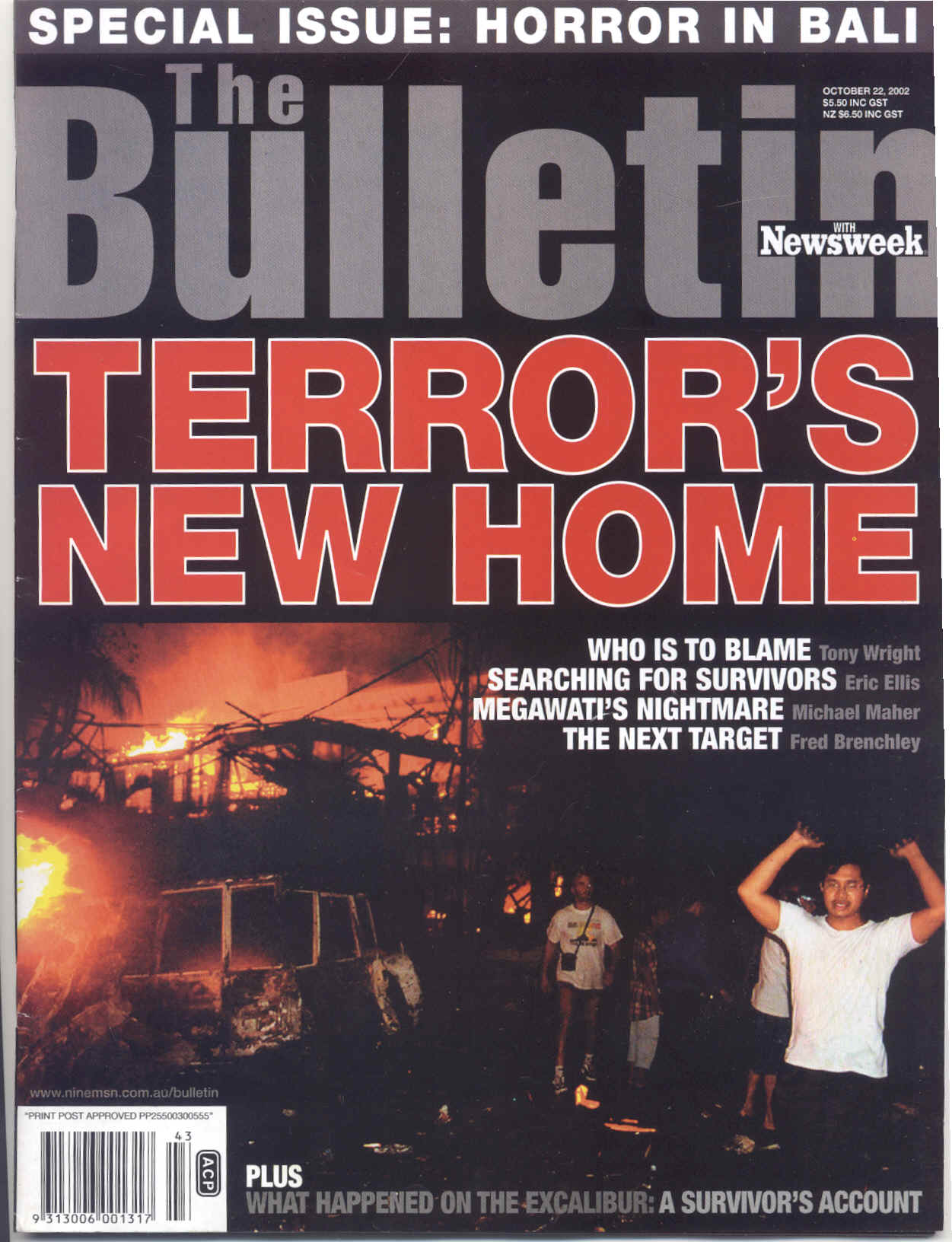

Winner of the 2003 Walkley Award, Asia-Pacific reporting….

THE Bali bombers were rootless young men recruited from the dusty poverty of a village in West Java – their overseer a worldly West Javanese, burning with Islamic zeal and with the contacts to organise and bankroll their jihad. Eric Ellis retraces their steps as they moved from village to town meeting the fixers, financiers and bombmakers, and finally assembling and detonating the devices that would kill and maim so many in a Kuta Beach tourist precinct.

March 5, 2003

GROUND ZERO

“Slay the idolaters wherever you find them. Arrest them, besiege them, and lie in ambush everywhere for them” – The Koran, chapter 9, verse 5

IT’S 11.06PM ON SATURDAY, October 12, 2002 and the Sari Club is a United Nations of Idolatry. There’s much devotion being afforded to the free-flowing VB and Bintang. A strong smell of dope hangs in the air. And some serious body-worship is in the offing when the club winds down at about 3am. Just another normal night in Kuta, Partytown Central.

Corey “Goose” Paltridge, 20, nicknamed for his Top Gun hero, is one of 500-odd revellers from 25 countries at the Sari Club and Paddy’s, the infamous meat market of a bar just across Jalan Legian. Goose is partying hard. The glazier is on his first trip abroad with the Kingsley Football Club in Perth. Eminem’s Without Me is pumping through the speakers. Goose plays air guitar in front of his mates.

Marc Gajardo is more discriminating than Goose. “I’m sorry, but I really can’t dance to this,” the 30-year-old English surfer tells his girlfriend Hannabeth Luke and friend Melanie Cohen when the Sari DJ plays Cher’s Believe. With mock disgust, Marc heads for Jalan Legian.

He steps outside for some fresh air. Standing there, he may notice that a white Mitsubishi L300 van is parked outside the club. He may even notice the 12 filing cabinets packed inside – late Saturday night is a strange time to deliver office furniture. More likely to catch his attention, in Bali’s equatorial heat, is the young Indonesian man who steps from the van into Paddy’s wearing a very heavy vest.

The man is dressed for jihad, his vest bulked up by 5kg of TNT. Inside the van’s filing cabinets are 48 draws packed with a lethal 700kg recipe of potassium chlorate, sulfuric acid and aluminium powder – a powerful bomb primed for maximum destruction. At 11.07pm, the man in the vest blows himself up. Thirty seconds later, the Mitsubishi goes up too, possibly with another man in it. The times are known because the blast was so big it registered on Indonesian seismographs. Marc takes the full force of the bigger second blast and dies instantly. Goose perishes in the fireball that engulfs the thatched-roof Sari Club. Beth and Mel crawl from the inferno and survive. In all, 202 people will be killed and 350 horribly burned or injured.

In the next few weeks, in a Denpasar hall that will double as a courtroom, 25 Indonesians believed responsible for those bombs will answer for the attacks. If found guilty – and many have already confessed – death by firing squad awaits most.

And for the attack’s alleged masterminds – Mukhlas, Imam Samudra and their principal accomplices, who had cased the two clubs in the week earlier – their part in the jihad will have been splendid. For Islamic militants like them, a death killing unbelievers guarantees glory before Allah. Paradise will have been entered.

THE TREE

“Do not make mischief on the Earth” – The Koran 29:36

THE TINY TOWN OF MALIMPING, in the remote corner of south-west Java, revolves around its alun-alun, the village square as big as a football pitch common to many Javanese towns. The Indonesian state gathers around it; a police station, a school, a health clinic, municipal offices and the Telkom exchange. There’s also a mosque and the local wing of Vice-President Hamzah Haz’ Islamist United Development Party. The merah-putih, Indonesia’s red-and-white national flag, flutters proudly above.

And in the middle of the alun-alun is a massive asem tree. Malimpingers have shaded under their illustrious tree for generations; to pray, plot against Dutch colonisers and Japanese occupiers, celebrate the Merdeka (independence) of 1945, Suharto’s ousting in 1998, or simply to play guitar, gossip and while away the scorching equatorial days.

It was beneath this tree’s weeping boughs that 35-year-old Imam Samudra recruited jihadis to his holy war, just 50 metres from Malimping’s unsuspecting police station. “We had no clues they were there, no hint that anything suspicious was going on,” says a slightly embarrassed police chief Jamalludin Chaniago. “It was an entirely normal place to be.”

Samudra made the bus journey to Malimping from his home in Serang, five hours’ drive north, in mid-2000, not long after he returned to Indonesia from 10 years abroad in Pakistan, Afghanistan and, mostly, Malaysia. Outwardly, he wanted to look up a wealthy friend he knew from Malaysia, a man called Ook Oktavia – or Pak O.O. as he’s known in Malimping. Pak O.O. is the go-between unskilled Malimpingers see when they want to work in Malaysia, in jobs Indonesia doesn’t have, and for wages three times those they can earn at home.

The Oktavia-Samudra association was natural. Both come from West Java and speak the region’s Sundanese as their mother tongue. But there was another link: Oktavia’s 20 year-old son, Andri. He also knew Samudra in Malaysia, where he worked after studies at Abu Bakr Bashir’s Al-Mukmin religious school in Solo, central Java, the notorious pesantren that authorities now believe is the base for Bashir’s Jemaah Islamiyah, suspected of being al Qaeda’s South-East Asian branch.

It’s clear that Samudra went to Malimping with more in mind than seeing old friends. His eldest sister, Aliyah, told me that when he returned to Indonesia at Eid, the end of the Islamic haj pilgrimage, “he felt hurt and angry”. “He’d seen his Muslim brothers slaughtered [in Afghanistan and Palestine] and he wanted revenge for that,” she says. Inspired by the Taliban’s success in creating a pure Islamist state in Afghanistan, spurred on by the brimstone of his compatriot cleric Bashir, and seeking revenge for attacks on Muslims in Ambon, Samudra had terror on his agenda.

Older, fluent in English and Arabic and full of worldly adventures in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Samudra cut a thrilling figure for impressionable kids like Andri, his friend Andi – one of Malimping’s young football stars who lived just 50m from Andri Oktavia’s house – and an acquaintance, Arnasan, who lived in his parents’ shack outside town. Over two years, he introduced his new friends to computers and the internet, teaching them how to communicate online. He acquainted them with mobile phones, with SMS. He explained the “victory” of September 11.

They would meet under the tree and then stroll over to the mosque to bond in prayer. Gradually, Samudra got to know these small-town boys with barely an education between them, winning their trust and playing on their circumstances, their vulnerabilities. They didn’t realise it but Andi, Andri and, particularly, Arnasan were Samudra’s low-hanging fruit, forming the core of what would eventually be the 13-strong Banten halaqah, named for their home region in West Java. Halaqah is Arabic for an Islamic study circle but, in truth, Samudra had formed a terror cell that police now know as the “Serang Group”. Members of the group have been implicated in bombings across Indonesia, notably the Christmas 2000 attacks on Christian targets in eight cities. Bali wasn’t yet marked for attack but the boys sensed their guru was planning something big, something that would guarantee them eternal paradise. It was exhilarating stuff for three naive kids from a scruffy town like Malimping.

By early 2002, after a crucial meeting in Thailand between JI’s leadership – which included Mukhlas and, by some reports, Bashir – and known al Qaeda operatives, it was decided to bomb “soft targets” in South-East Asia, because the hard target strategy was now too difficult after the rumbling of the Singapore attack plan in late 2001. Samudra’s Bali plans took off. A meeting of the Serang Group at a safe house in nearby Bandung decided the matter. Bali and its corrupting foreigners would be the target of a big hit.

Ambitious terror is expensive. At the Bandung meeting, the plotters decided to finance their jihad by robbing non-believers. Stealing from infidels was not a crime, Samudra explained to his charges, but a noble part of the holy struggle. On August 22 last year, Andri and Andi donned balaclavas and pistols to raid the Toko Elita Indah jewellery store in downtown Serang of $A80,000 in cash and gold. It helped that Elita’s owners were Chinese, regarded by many Javanese as polluters.

Samudra didn’t participate in the Elita hit but Vini Khian, the store owner’s 18-year-old daughter who was shot in the abdomen during the hold-up, told me she’d later recognised him as the suspicious man who cased the shop in the weeks before the raid. He would repeat the tactic six weeks later in Kuta, scouting Bali’s foreign tourist precinct in the week before the October 12 attack, looking for the target with maximum impact.

A few days after the Elita grab, most of the loot was handed to Samudra in the back of a Suzuki van parked in a Jakarta bus terminal. Andri, Andi, Arnasan and another cell member, Abdul Rauf, kept some to rent two safe houses near Serang, finessing their plans and staying close – but not too close for suspicion to be aroused – to their guru Samudra.

One of the tenancies, unit 316 on the Ciruas road 6km from Serang, cost 60,000 rupiah ($A11.15) a month. The apprentice terrorists got what they paid for. The unit is not even a studio, but a filthy 2m x 3m room in a motel-style block of six. Bizarrely, someone has fashioned a Star of David from masking tape on a pillar at the unit’s entrance. Indonesians know such accommodations as kos, a Dutch holdover term for shared lodgings. Indonesian kos are a focus of social life, which parents grumble is why it takes so long – up to 10 years – for their kids to finish university. But not this one. “I barely saw them,” says 42-year-old landlord Sunarto. “They would come and go in the night, creep around.” Sunarto is still not happy with the “college students” who rented the room. “They used my room to plan this terrible thing. I really want to beat them up.” Sunarto says they paid two months’ rent from August. The last time he saw them was early October. He’s still waiting for the rest of the rent.

Andri, the Malimping slave trader’s boy, was captured a month after Bali. He’s now imprisoned in an even smaller room than the hovel he rented in Serang and, unless his influential father can swing it, facing another 15 years there. Andri’s friend, Andi the football hero, could get the death penalty, despite shopping his hero Samudra to the police in November.

And what of Arnasan, the poorest of the three? At 11.07pm last October 12, as Marc Gajardo was avoiding Cher in the street outside the Sari Club, Arnasan transformed himself into “Iqbal” and became South-East Asia’s first suicide bomber. Samudra had delivered on his promise of paradise.

THE PREY

“They are to cohabit with demure virgins … as beauteous as corals and rubies … full-breasted maidens for playmates … in the gardens of delight” – Koran 55:56,58

ARNASAN’S PARENTS HAVE NOW accepted their youngest son’s role in the Bali bombings. They have little choice; they haven’t seen him since August last year, when he told them he was off to see “a friend in Serang”, most likely Samudra. That’s also about the last time they saw Arnasan’s insistent friends from town, Andi and Andri. The next outsiders to come to their padi house were police from Indonesia and Australia, who took DNA samples from them in November to help identify the body parts that had bomb debris attached to them and which were found in the Legian rubble – the remains of their youngest boy.

Three nightmares have convinced Arnasan’s 57-year-old mother, Arti Satra, that her son is dead. In the first dream, before the bomb, she saw Arnasan fall down. In the second, around the time of the Bali bombs, Arti dreamt she saw her son’s only pair of trousers, with legs but no upper torso. The third dream was after the bomb but before the police arrived at her door. In it, Arnasan was dead. Says her husband, Haji Satra, also 57: “I am convinced now. It’s obvious to me that my son has died. This is Allah’s will.”

Arti says Arnasan was educated only to primary school, after which he was forced to drop out because his family could not pay school fees. “He was a little bit naughty when he was young; he liked to play more than study,” she says. “But he was a good boy. He was quite devoted, prayed five times a day and always observed Ramadan, but never expressed any extreme views. If I had known Arnasan wanted to do such things, I would try as a mother to ask him not to do it.” She repeats it over again, perhaps three to four times, breaking down more deeply each time. “In my heart I am always crying. I keep crying and crying and looking at nothing.”

The family’s poverty is striking. Their wooden hut is little bigger than the average Australian bathroom. There’s no electricity and few possessions. Food is provided by a single rice padi, shared with a neighbour. A few chooks scratch around in the dust. Arti and Satra can’t even speak Bahasa Indonesia. In Java’s remote backblocks like Sundanese-speaking Malimping, to speak disparate Indonesia’s unifying national language suggests a basic education neither ever had.

Sobbing, Arti still holds some small hope that might be expected of a mother. “Whenever I see the police coming, when I see the uniforms walking through the padi, I think they might be bringing my son back to me,” she says, as scrawny cockerels scratch around her and the flyblown infant grandson she’s nursing.

But today, all the Malimping police are bringing to the parents is a routine surat, a statutory declaration that requires their identifying fingerprints. Pressing their thumb into the police inkpad, and then to the surat, theirs is an absolute submission to police authority. The document is blank but even if there were writing on it, the illiterate couple would have no idea what it said. Likewise the letter, reportedly from Arnasan and found at his friend Andri’s house, in which he apologises for his “martyr’s death”. “I want to say sorry to you, but all I want to do is commit myself to jihad,” he wrote.

THE ZEALOT

“God’s curse be upon the infidels! They have incurred God’s most inexorable wrath. An ignominious punishment awaits the unbelievers” – Koran 2:92-6

WHEN IMAN SAMUDRA was a boy in the 1970s – before he became a mujahid with al Qaeda and the Afghan Taliban, before he joined G272, a fundamentalist group of 272 Indonesian veterans of the Afghanistan conflicts, and before he settled in Malaysia as a computer technician – he was called Abdul Aziz. The eighth of 11 kids, he came from Serang, a market town in the West Javanese region of Banten. And Abdul Aziz was a cengeng. In Bahasa Indonesia, a cengeng is a crybaby. As in English, it’s not a particularly flattering term. Samudra’s 42-year-old eldest sister Aliyah Rudi doesn’t remember their childhood with much attachment. “I always had to carry him when he was a baby. He would cry very easily at the smallest thing.

“There were no happy times,” she says. “We were always poor. Misery came after misery. We always live in misery. We always had hard times but I consider this a test of Allah.”

She’s still miserable but her brother’s actions, of which she’s “very proud”, provide some definition. “My brother took the right path,” she insists. “I believe in his goal to bomb Bali.” She describes her brother as an intellectual, a studious man with eclectic interests who excelled at school, topping his class each year during his time at high school.

We’re sitting on the patio of this severe woman’s small house in a Serang slum. The Serang-Banten region resonates in Java’s history, in its politics, its religion and its mysticism. Banten’s mosque, Indonesia’s oldest, is almost 500 years old, a place of pilgrimage for the country’s Muslims, who believe it has mystical healing qualities. The area was also the first landfall in Java of the Veerenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the Dutch East India Company that led the 350-year Dutch colonisation of the islands.

The area’s mysticism echoes beyond the province. Suharto’s bodyguards tended to be Bantenese, bestowing that extra magic to keep evil from their president. Desperate for some of his lustre, Suharto’s incompetent successor, B.J. Habibie, raised his special militia from among the Bantenese.

Samudra’s sister is the most covered woman I’ve seen in years of travel through South-East Asia, clad in traditional Islamic dress, a blue tent that’s just a face-mask short of a burqa. Banten is Indonesia’s most devout region, a stronghold of Darul Islam. DI extremists violently campaigned for a Taliban-style Islamic regime in post-colonial Indonesia. The intellectual Samudra’s high school teacher was a DI hothead. Today, DI leaders obsess the terrorist-watchers of agencies like the FBI, CIA and the Australian Federal Police.

A goods train rumbles past barely 50m away from Aliyah’s house, en route to the nearby state steelworks that showers pollution on the district. A mosque is 50m the other way. While Aliyah’s home is concrete, her neighbours’ are mostly shanties and lean-tos. Before Bali, Aliyah was known for her sate bandeng stall, grilling the milkfish named for its succulent white flesh. But since Bali, her fame has been transformed into something more profound. Delighted neighbours give her the thumbs-up sign as they walk past the house. “No one has been against my brothers.” She smiles. It’s her only animated gesture in 30 minutes of difficult conversation. The smile doesn’t last. “The little boy dares to fight against the old man,” she rails. She means her brother, fighting for the masses against the US and its allies. “He is a defender of Muslims in Indonesia, a defender of peace. Everybody knows that his purpose is only for jihad. We are not terrorists but it is a war on kafir.” She almost spits out the Arabic word for “unbelievers”. “What he did was just to scare people.”

THE DEVOUT

“You shall sing the praises of your Lord, and be with the prostrators. And worship your Lord, in order to attain certainty” – Koran 15:98-99

WHILE SAMUDRA, in West Java, was plotting deadly ways to scare kafirs, in a tiny hamlet on the eastern side of Indonesia’s main island, a family of devotees were spreading their own brand of hatred. Foreigners don’t get a friendly reception at the Al-Islam boarding school in Tenggulun run by the eldest son of former village elder Nur Hasyim – the father also of the radical fanatics the world now knows as Amrozi, Mukhlas and Ali Imron. Not surprisingly, visitors are welcomed by signs in English that say “Only for Muslim People”. The elementary English taught to students here is not the standard “Hello” or “How are you?” but words like “avenger”, “mole”, “accuse” and “spy”. At least, that’s the lesson for today on the blackboard – as much as I could see before I retreated under a torrent of spittle.

Tenggulun itself is almost medieval. A few of its hundred-odd houses have been tarted up by remittances sent from relatives working in Malaysia but, like Iqbal’s district in West Java, the poverty is palpable. There’s hardly a car or a motorbike on its streets. Wizened old men, their backs bent under cut bamboo, stagger through town herding buffalo. From a dilapidated mosque, a muezzin wails out a strident midday call to prayer.

The windows at the school’s other “campus” – which Amrozi was in the process of setting up and which was the place where he met Samudra – are filthy. In the dust, anonymous fingers have written messages of support for the brothers in English and Bahasa: “Bali for the jahanam (evil)” and “Bali for the neraka (hell)”, “Amrozi group for Paradise”. There are Koranic blessings, and promises of sugar and heavenly liaisons with Balqis, a mythical Muslim beauty of great power.

Two doors from the mosque is the house where Amrozi, Mukhlas and Ali Imron were raised. It’s small and modest, more a wooden shack, with its three “rooms” partitioned by flimsy plywood. There’s a small refrigerator (containing an egg, two half-eaten chicken legs and a bottle of water), a fan and four broken rattan chairs.

Groaning in pain in the middle of the stone floor is the family’s 85-year-old patriarch, Nur Hasyim. The word “patriarch” suggests a towering authority figure. But not this sad man. Not any more. He lies on the floor in a puddle of his urine, incontinent and whimpering. His wife swats away flies crawling over him, occasionally adjusting his green sarong to cover his shrivelled genitals. The stench in the house is overpowering. In the street outside, one of his grandchildren – a girl no more than five – rides a tricycle. When the wheels turn, the trike’s tinny speaker plays London Bridge is Falling Down.

Tariyem, the 65-year-old mother, is herself a frail little thing. She’s very welcoming and gives me the honorific bapak, even though I’m a generation her junior. The house has been raided a dozen times since October 12, she explains, including by Australian police. “They were very kind,” she says. “They gave me 50,000 rupiah for our information. They took lots of cassettes and magazines and discs.”

She seems genuinely bewildered by the whirlwind that’s swept in since October 12, a tragedy that will likely see a quarter of her family executed. “Why would my kids do such a thing? I cannot understand. They were all good kids. They never expressed any hatred for anyone.

“I just have to accept that they were involved. We don’t have anything. The only thing we have is religion. I hope that their struggle can be accepted by Allah. I just have to surrender to Allah.” Like Arti, Iqbal’s similarly devastated mother in Malimping, Tariyem breaks down. The two women – one has already lost a son, the other will probably lose three – don’t know each other. But they are united in grief and confusion. Tariyem is still sobbing as I leave, pleading: “Help us bring back our boys.”

THE FIXER

“We do not send down the angels except for specific functions” – Koran 15:8

EVERYONE IN INDONESIA needs a fixer. They’re the access merchants who open doors, arrange stuff, get things done – for a modest fee, of course. Foreign journalists and diplomats couldn’t function without them. Working the angles, and knowing everyone’s mobile number, fixers provide function in the chaotic shambles that is often Indonesia. The best fixers are influential and so low-key as to be almost invisible.

In the central Javanese city of Solo, the Bali bombers had Herniyanto. Except the 25-year-old teacher at Abu Bakr Bashir’s Al-Mukmin pesantren didn’t get paid for his fixing. His fee for organising the safe houses, the transport, target maps (of military origin) and many of the jihadis’ meetings was October 12. And he fixed it all while his young wife was pregnant. (She gave birth to a son three weeks after the boy’s father was captured last December 4.)

If the conspirators needed motivation, Herniyanto was eager to please, producing Bashir’s cranky sermons to fire up the expanding group. He organised video nights for the plotters, with Osama bin Laden’s A Martyr’s Testament: Five Mute Witnesses to the Brutality of America the Terrorist the gripping main feature. It’s an al Qaeda documentary about the treatment of its detainees at the US military base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. If that was too depressing for the Bali-bound jihadis, there were videos of the September 11 attacks for inspiration.

Fixers also have a keen sense of who’s boss. And in terrorism as in normal life, real estate is a telling indicator. Of the six houses raided by Solo police, the biggest and most expensive was Samudra’s. His place is in Solo’s middle-class Sukoharjo neighbourhood, a pleasant concrete cottage gaily painted in a pinkish hue. The roof, recently repaired and painted the green of Islam, pleased him. Herniyanto paid a year’s rent, 1.7 million rupiah in cash, in advance, to move Samudra in.

It’s standard procedure in Indonesia for tenants to show landlords identification papers. Samudra was careful to keep his secret, apologising to his 43-year-old neighbour, Ani Ratno – whose family owned the house – that “my friend Herniyanto has them”. She says Samudra moved his wife and four children to Solo in August. Ani Ratno thought them “good neighbours, very religious. The house was very crowded sometimes.” She rarely saw Samudra, who would come and go at night. His wife said he was “very busy working with computers”. Most days, Ani Ratno’s children played with Samudra’s.

Herniyanto had planned with convenience in mind. Samudra’s Solo digs were just a short stroll from the homes of fellow conspirators Dulmatin, one of the suspected Bali bombmakers, and Ali Imron, Amrozi’s and Mukhlas’ brother. After the Bali bomb, when Samudra’s identikit was displayed on national TV, Istiqorma, the five-year-old daughter of Dulmatin’s neighbour, noticed that the face looked a lot like “Sabillah’s daddy”. It was. When strolling around the block to plan terror, Imam Samudra liked to take his four-year-old daughter along, too.

The three houses, just 100m from each other, were also a short three-wheeled becak journey from the vacant house of Herniyanto’s in-laws, where neighbours say as many as 15 men would come for Koran readings from June to October, mostly at night. Susi, 31, runs a warung across the road which sells, among other things, box-cutters. She noticed activity around the house just two days before it was raided by police in November, well after the Bali bomb. She’s suggesting the inhabitants may have been tipped off. Police also raided two nearby terrace houses, including the home of Herniyanto’s brother, which police now believe was the group’s operations centre. Lots of JI documents and al Qaeda videos were seized here.

HEAD OFFICE

“Carry out the orders given to you” – Koran 15:94

SOLO IS WHERE INDONESIANS go to connect with their inner Java. The city’s famous kraton, the ancient sultan’s palace, is stunning. So is the Masjid Agung, the grand mosque built, not in the common Arabic style, but in a low-slung Javanese manner. And chaotic Klewer Market, the centre of the world’s batik industry, is an absorbing jumble of colour and fabric.

But it wasn’t a cultural odyssey that Samudra and his Serang Group from West Java, and the brothers Amrozi, Mukhlas and Ali Imron from Tenggulun village in East Java, took to Solo last August. It was to finetune the attack on Bali, in the city that is home to the fundamentalist Jemaah Islamiyah of hardline cleric Abu Bakr Bashir, who had taught many of them while exiled in Malaysia during the 1980s and 1990s.

Samudra first contacted Amrozi in late 2000, not long after his return to Indonesia from Malaysia. He needed bomb ingredients for church attacks in Ambon. The younger brother of Ali Ghufron (better known by his nom-de-guerre, Mukhlas), another powerful G272 jihadi also influential in JI whom Samudra knew from Afghanistan and Malaysia, was eager to help. This time, however, he was summoned to Solo.

When Amrozi arrived, he had no inkling Bali would be the target. For Indonesia’s radical jihadis, the peaceful Hindu island and its infidel tourists were doubtless a provocation to their ideal of an Islamic super-state from Thailand to Timor. But they were pragmatic enough to know their war would not be easily won. Bali, with air links nearly as good as Jakarta’s, was a convenient – and unsuspecting – hub to source and store materiel for campaigns further afield.

Samudra welcomed Amrozi over soto at an Islamic community centre outside Solo known as a JI haunt. They arranged another meeting at the Klewer batik market, when Samudra brought along Idris (also known as Jhoni Hendrawan) and Dulmatin, two bomb-making and electronics experts. They told Amrozi what they needed. As in Ambon, Amrozi would be the quartermaster, and the mule, knowing only as much as he needed. But this time the quantities would be much bigger. A van was also needed and it should all be delivered to Bali by late-September.

Samudra handed Amrozi the funds; the equivalent of $A10,000 made up of rupiah, US greenbacks, Malaysian ringgit and Singapore dollars, the mix of currencies suggesting their funding wasn’t entirely from the jewellery store heist in Serang. However another credible source maintains the funds were not actually handed over until a later meeting in Tenggulun. Surrounded by Klewer’s dazzling batik, Amrozi was told Bali was the target, and assured that victory would be glorious. It was a successful meeting. The jihadis strolled across the road to give thanks at the Grand Mosque.

The operation was developing quickly. Samudra told his wife they would soon be moving. Their neighbour Ani Ratno says the wife told her they were moving to Lampung, the same Sumatran town where Herniyanto’s Solo-born in-laws live. On October 8, the Samudras moved out. His wife headed west with their four children, and Samudra east. He had important business in Bali.

THE EXECUTION

“Your Lord never annihilates any community unjustly, while its people are unaware” – Koran 6:131

URCHINS GATHER ON the upper decks of the decrepit boat that ferries traffic from Java on the hour’s passage to Bali. For 3000 rupiah, the scamps swallow-dive into the murky water 30m below, then duck for the coins delighted passengers fling as the ferry retreats from the port. Their antics introduce a holiday air to the journey. We are, after all, heading for Bali.

Amrozi made the journey in late September, with a white Mitsubishi van in the hold, bearing a deadly chemical cargo. Today, several months after the bombings, a car like this would be impounded by soldiers toting sub-machineguns, its occupants arrested. The patrols began on October 25; before that, security was non-existent and, besides, vehicles carrying explosives were commonplace. Balinese fishermen use them instead of trawling.

After the meetings with Samudra and friends, Amrozi set about his important assignment. He was also eager to please his intense elder brother, Mukhlas, who had long regarded Amrozi and his faith as a bit flaky. Amrozi had bought a white Mitsubishi L300 van from a man called Annas in Tuban village in East Java, not far from Tenggulun. Annas told the police Amrozi had offered him Singapore dollars and Malaysian ringgit for the vehicle. Amrozi converted the cash to rupiah and paid Annas around Rp30 million (about $A5000).

Amrozi drove it into Surabaya – Indonesia’s second-largest city, about three hours from Tenggulun – to the Tidar Kimia store of Chinese chemical merchant Silvester Tendean, where he’d filled Samudra’s Ambon order in 2000. Tendean was keen to deal and happily doctored invoices that showed Amrozi had bought cooking salts. Arrested soon after Amrozi, Tendean is now on trial in Surabaya for his role in various terror campaigns. His store is shut down, but on Jalan Tidar, there are perhaps 20 just like it.

Amrozi set out for Bali, seven hours by road and ferry. As he drove, he may have even passed the truck which has one side decorated by a portrait of a smug Osama bin Laden surveying his jihadis flying a plane into the World Trade Center, the other that classic Easy Rider biker image – mixed symbolism if ever there was. At Banyuwangi, he paid Rp40,000 car-and-driver passage. An hour later, he arrived in Bali.

While Amrozi was gathering the bomb materials inJava and making his way to Bali, the fixers were at work in Denpasar. Safe houses were rented in at least four locations. The main one was a flat at 18 Jalan Menjengan, where Samudra stayed. Landlord Mas Edi rented the flat in September to an “Alfian”, a man with a strong Batak accent, meaning he was from the Medan region of Sumatra. Alfian’s ID said he was born in 1976. He told Edi he needed the flat for a year to store cargo. He paid a year’s rent in advance, some Rp10 million, wired through Bank Mandiri. “He found it through the newspaper,” said Edi. “I gave him the key … and he still has it.”

Edi’s ground-floor flat had a mango tree out front. A young student neighbour remembers one afternoon during the week before the bomb, Samudra yelled out to her: “Do you like mangoes?” He picked one and, now flirting, gave it to her, suggesting she make a rojak. “He was nice, very polite and had a caring manner. His face is not scary, I don’t suspect him capable of doing such an act.” It seems the charmer Samudra was good at picking low-hanging fruit.

Amrozi arrived in Bali during the last week of September, checking into Room 101 at the seedy Hotel Harum, a flophouse in central Denpasar. His brother Ali Imron told police he arrived about the same time, accompanied by Dulmatin and another man, a Malaysian called Dr Azhari who’d also been in Afghanistan. The bomb-making team were in place.

Ali Imron says he packed the explosives into 12 plastic filing cabinets, each with four draws. He roped the cabinets together with a plastic tube containing explosive, priming the package with dozens of detonators. The bomb was packed into the van delivered by Amrozi, who then returned home to Tenggulun. A bomb vest was also built: six pockets of a vest filled with plastic PVC tubes containing TNT, and wired to a switch to be flicked by the wearer.

Ali Imron told police he prepared four detonation options: a remote-control device activated by a mobile phone; a standard countdown timed for 45 minutes from activation; switches; and a detonator that automatically engaged when its lid was removed. If Ali Imron’s version is correct, it’s clear there was mistrust in some of the operatives. Ali Imron devised the first two methods as failsafes if the deliverer suddenly opted out.

The Mitsubishi was driven to Jalan Legian, which had been scouted and selected by Samudra as the target zone. Samudra was reportedly praying at a nearby mosque. Ali Imron says he was accompanied by two men, both known by their nom-de-guerre of Iqbal. One of them was Arnasan, the poor boy from Malimping.

Just before reaching Legian, Ali Imron left the van and jumped on a motorbike left there by his colleague Idris. Arnasan drove the van to the Sari Club, and stayed with it. Iqbal put on his vest and, at 11.06pm, stepped from the van toward Paddy’s. While Samudra maintains there was only one suicide bomber – Arnasan, who was wearing the vest – Ali Imron’s version contradicts this and says there were two and that Arnasan stayed in the van. Whatever the real identity of the vest-wearing “Iqbal”, he could hear Eminem’s Without Me booming from the Sari Club behind him as he climbed out of the van.

“Jump back jiggle a hip and wiggle a bit

And get ready cuz this is about to get heavy …”

– Eminem, Without Me

THE DEALMAKER

“The noblest of you before God is the most righteous of you” – Koran 49:13

IT’S LUNCHTIME IN A Jakarta hotel. One of Indonesia’s most influential lawyers sweeps into the cafe. He is neither garbed in the flowing robes nor clutching the Koran one might expect of the “Muslim Lawyer” his business card describes. Natty in good suit and expensive haircut, this senior counsel with the Indonesian Muslim Lawyers Group seems more Salomon Brothers than Sharia. We’re lunching because he’s defending some of the alleged Bali conspirators. There’s much to discuss. The lawyer remarks he’s taking the case pro bono, which I take to mean that I’m paying for lunch. But conversation is a struggle. His mobile phone or, rather, phones – he has three and his assistant two – won’t stop chirruping. The one with a French Can-Can ringtone is particularly distracting.

Between juggling Nokias and forkfuls of nasi goreng, he explains why he’s taking the case. “I must ensure it is fair, that it doesn’t become the target of infiltration and external influence,” he says, a noble ambition in a country where the law is derided as the best money can buy.

His clients, of course, are innocent; he reels off the usual Mossad-and-CIA-did-it theories. He claims the Legian bombs were “micro-nuclear”. whatever that is. He’s not sure himself but “Americans know about it. They are the crusader nation”.

He’s going to have to do better than this. “My clients’ so-called confession is their religious duty, because they do not think it is wrong, it’s best for their religion. There is a reward of going to paradise. A confession under Allah and under the law are two different things. The case should be built on the facts. I want to leave religion out of it.”

Lunch dishes cleared, he pushes a school exercise book across the table. It is, he explains, Imam Samudra’s hand-written diary, written in his Denpasar cell since his arrest.

Samudra has filled about 24 pages, mostly in Bahasa. He writes in Arabic after prayers and in English, he spouts invective. Exclamation marks scream from the generally neat text – BUSH! HOWARD! AMERICA! AUSTRALIA! TERRORISTS! The diary reveals a sarcastic man, angry and unrepentant. He complains bitterly of the police and their choking kretek cigarettes, and disparages their interrogation. Their questions are “childish” and “stupid”, the investigation “ridiculous” and “boring”. There’s no confession in the pages I read, nor accounts of torture made in the Indonesian press. Just plenty of bile from a cengeng.

“So, Bush the ‘Pharoah’ [the same ironic term Osama bin Laden uses to describe the US president] and the ‘so-called’ John Howard congratulate Indonesia for success in capturing terrorists. But the terrorists are those who treat the Muslim brothers like animals, those who bombarded Afghanistan during Ramadan after September 11, 2001.

“To the infidel, when you stir up trouble, you will be led to hell. Sooner or later, there will be torture for you in the world, and even the afterlife will be messed up.”

Cynicism drips from Samudra’s acid pen: “The animal Bush declares this is a crusade, for infinite justice, and joining him is the ‘nation’ called Indonesia in which the majority are Muslim. Yes, of course America and Australia are correct, that’s why Muslims are rounded up in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia for the sake of the master America and their lackey Australia.

“Allah will vanquish and destroy America and other infidels. Those who make war on Allah’s enemies, on those infidels who slaughter Muslims, that is called jihad. Yes, of course, America and Australia are correct.”

He also shows an inventive grasp of current affairs: “the terrorist America is definitely successful at cloning because they have spread out ‘Islamophobia’ and ‘Jihadophobia’ in the veins and the blood of the Indonesian people. That’s why all the ridiculous procedures that America imposes are cloned and followed by the Indonesian government”.

In one entry, written after a day with police reconstructing meetings with alleged co-conspirators, he puns thathe is an actor in a “REKONSTRUKSINETRON!!!” (Rekonstruksi is Bahasa for reconstruction and a Sinetron is an Indonesian soap opera.)

“The police are the directors and scriptwriters and I am just the instant actor that must follow all the rules; no complaints, just follow the director, my mouth sealed.”

His English seems solid. “I.M.A.M S.A.M.U.D.R.A” is defined with initial capitals as “Islamic Movement against American Monster. Save And help our Masjidil Haram [mosque worshippers] UnDeR Attack from American aggressors and its allies.”

It’s gripping stuff, a solid scoop, but before I can read more, the lawyer grabs back the book. “Perhaps we could come to a mutually beneficial relationship.” He suggests we should keep our “negotiations” confidential.

“It’s very expensive for my team to always be travelling to Bali to talk to clients,” he grumbles. He proposes an “arrangement”, exclusive stories and access to Samudra for $US2000. Like any practised dealmaker, he throws in a sweetener, a video of Samudra being interrogated by Indonesian police and “guarantee” of an exclusive interview in his Bali cell. “It can be arranged.”

“Many wartawan [journalists] from your country want to deal with me,” he claims. “… if you don’t want, I sell to them.”

The Bulletin declines his offer. We’ve seen enough. It’s time for justice to do its work.

Additional research by Rin Hindriyati, Jakarta

Rupert Murdoch

Rupert Murdoch nm @enem408

nm @enem408  Mark Stephens @MarksLarks

Mark Stephens @MarksLarks