THEY lurk in the shadows of every autocracy, monopolising business deals and jealously guarding their access to the political power that provided them. In economies across Asia and the Middle East, they’ve become a virtual proxy for the dictators crucial to the massive commercial fortunes they’ve built, often impervious to legal sanction. Positioning themselves as gatekeepers for foreign investors, they are also impossible to avoid but are often an impediment to competition and growth.

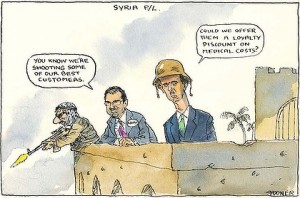

More than cronies, they are people like Syria’s Rami Makhluf, multibillionaire first cousin to Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian dictator whose goons are now killing his countrymen to maintain his family’s 40-year hold on power.

Makhluf was born two years before his uncle Hafez, Bashar’s father, seized power in Damascus in a presidential palace coup. Now he is Syria’s richest person, regarded as the most influential economic figure in Syrian business. The BBC recently included him as one of the eight key figures in the embattled Assad leadership circle – and by several decades the youngest – quoting analysts as saying ”no foreign companies can do business in Syria without his consent”.

Australian investors in Asia have seen this intoxicating masala of politics and money before, and have been caught – or perhaps had no choice – doing business with them if they want to get set in the booming region.

In Indonesia, it has become a virtual rite of political passage for relatives of leaders to amass huge fortunes in business without much in the way of deal-making skills, (pace the Suharto clan and the corporate leeches that surrounded Megawati Sukarnoputri). Malaysia’s feisty blogosphere asks whether the fast-growing CIMB Group would be Malaysia’s second-biggest bank and its chief executive, Nazi Razak, one of the country’s richest men if he wasn’t the current prime minister’s brother or the youngest son of a sainted former PM. Singapore has the members of the Lee family, who gather around state-owned investment house Temasek, and Thailand its fabulously wealthy amart, the quasi-aristocratic elite, and the billionaire Thaksin clan, who oppose them. It’s a sport among India’s business titans to manipulate deal-friendly ministers into office, and no self-respecting Burmese general hasn’t seen a bank or a logging franchise jostle he didn’t like.

But when people like Treasurer Wayne Swan exhort corporate Australia to get set in booming Asia and the Middle East, they don’t do so while warning of the pitfalls of teaming with someone like Rami Makhluf.

Washington does. After levelling economic sanctions on him and his family, the US Treasury described him as ”a powerful Syrian businessman who amassed his commercial empire by exploiting his relationships with Syrian regime members. Makhluf has manipulated the Syrian judicial system and used Syrian intelligence officials to intimidate his business rivals. He employed these techniques when trying to acquire exclusive licences to represent foreign companies in Syria and to obtain contract awards.” With interests spanning resources, banking, property and retail, the rentier Makhluf got his start in the 1990s, when the Hafez al-Assad regime handed him exclusive licences to operate duty-free stores across Syria.

But Makhluf’s best earner is SyriaTel, the dominant mobile phone carrier in a country with some of the most expensive phone tariffs in the developed world.

And how he got control of that is also revealing. With no skills in telecom, Makhluf joined Orascom Telecom of Egypt in 2001 in a joint venture to set up SyriaTel, a cosy deal that cost prominent opposition figure Riad Seif five years in prison and bankruptcy when he complained to parliament about its ”scandalous” terms. (It seems to help profits that Makhluf’s younger brother, Hafez, is the Damascus boss of Syria’s internal intelligence agency, the feared General Security Directorate.) But two years later, the Makhluf-Orascom venture had collapsed in recriminations and bitterness. Orascom officials describe an atmosphere of intimidation, which forced them out of the venture by 2003 but only after the Syrian side had availed itself of the Egyptians’ technical expertise. A lawsuit that went nowhere in the Damascus courts cited Makhluf’s ”persistent attempts to assume management control of SyriaTel with a particular motive to be able to sign solely on all bank accounts”. All of which may help explain why, with a GDP a head of barely $5000, Syria is among the poorest and least competitive of the Middle Eastern economies. It also explains why he and SyriaTel have been prime targets of pro-democracy campaigners laying siege to the symbols of Assad’s rancid dynasty.

Protesters across the country have specifically targeted SyriaTel outlets in their ongoing ”days of rage”. In echoes of the Tunisian protests that sparked the Arab Spring sweeping this region, the Syrian protests gathered momentum from February after 15 people were detained and beaten because they’d made public protests about corruption and exorbitant mobile phone costs.

In Tunisia, the revolution began when state thugs beat up a village trader trying to sell wares on the street. He set fire to himself and ignited a movement, which laid siege to the cosy family business ties, the Trebelsi and El-Materi clans, that had held back Tunisia.

The Makhluf clan are Syria’s Trebelsis and El-Materis. Tunisian strongman Zine El Abidine Ben Ali had long favoured his wife’s relatives in myriad government-linked business deals. Ben Ali’s 31-year-old son-in-law, Sakher El-Materi, became a billionaire with interests across telecom, car dealerships, property, media, shipping and banking, deals he lavishly self-celebrated though an eponymous website, Facebook page and across Twitter. Before Ben Ali fell in January this year, it was impossible to visit Tunisia and not make the billionaire El-Materi richer, just as it is impossible to commercially avoid Rami Makhluf.

Six months on, with the Arab Spring coming into summer in Syria, El-Materi is on the run, with Interpol on the family’s trail. His businesses have been seized and his websites have expired. As Syria burns and the Assads kill, people like Rami Makhluf and his clan relatives may well be asking if this is also their future.

http://www.theage.com.au/business/i-would-like-you-to-meet-my-cousin–20110609-1fuy6.html