October 17, 2002

As dawn broke on the chaos that was Kuta Beach, Eric Ellis searched for survivors of Australia’s worst terrorist outrage….

HE WAS tanned, a bit paunchy, late 40s; a handsome man with short hair. He was a solid bloke and very clearly an Australian. The bare feet and boardshorts – all that he was wearing – marked him out.

As we approached each other on the fourth floor of the Hard Rock Hotel on Kuta Beach last Sunday night, barely a block away from the Sari Club where our countrymen had perished in terror not even 24 hours earlier, I scoped him in that split second one spends assessing fleeting strangers. An old footballer on an end-of-season tear in Bali with the younger charges he’s now coaching back home? Or, just as possible, an ageing surfer on a nostalgic trip revisiting breaks he carved on the ’70s hippy trail through Asia?

And then he stopped, almost collapsing, grabbing the wall of the corridor for support and smothering his face with his right hand in a gesture of anguish.

“You all right, mate?” I called out. “No, mate, I’m not all right thanks,” he replied, almost impatiently. And then he broke down and wailed: “I’ve just lost … I’ve just lost … me daughter! I’VE JUST LOST ME BLOODY DAUGHTER.”

He said it twice but it didn’t need emphasising. I instinctively embraced this bloke I’d never met before, grabbing his neck and pulling his head into my shoulder as he sobbed uncontrollably.

“You poor, poor bastard.” It seemed such a pathetic thing to say. “I am so, so sorry.” He cried for about 10 seconds, contained himself and pushed free. Muttering his embarrassed thanks, he shook my hand and continued down the corridor, steadier this time. “Thanks, mate, I’ve got to find my wife.”

And that was it, a very human moment during a day when not much humanity was on offer. And perhaps even a very Australian moment when too many Australians, like this stranger, had lost loved ones. I didn’t get his name – it didn’t occur to ask.

IT WAS the hundreds of bags of crushed ice that first suggested something was very wrong at Denpasar’s Sanglah Hospital on Sunday. You saw the ice trucks lined up as you approached the clinic, the refrigerated ones borrowed from Bali’s five-star resort hotels, while the local Kijang trucks turned the dusty approach street into a muddy creek as the equatorial air quickly melted their cargo. Once inside the hospital compound, you could see – and smell – the urgent need for the ice.

A 20-man human chain had formed to ship the bags hand-to-hand from the parked trucks to the foyer. When the chain reached the foyer, a team of hospital orderlies, their white jackets spattered with blood and black ash, were casting the cubes on rows of charred bodies that had been piled up one on top of another.

It was a gruesome sight. People, mostly foreigners, gingerly picked through the remains. One victim, his mouth agape, was clad in what looked like a burnt sleeveless jumper in the black and red of Melbourne’s Essendon Football Club. Someone had the BBC World Service going on a short-wave radio. Alexander Downer was quoted saying only three or four people had been confirmed as being Australian. But it was obvious standing here, from the victims’ clothing and their loved ones’ accents, that the situation was going to be much worse. And then you remembered they were ferrying bodies to four other clinics around Denpasar.

At Sanglah, the ice was doing its job, for the moment. “We don’t have a big enough morgue to cope with this,” said one frantic orderly, Gede, as he doled out the ice. “There’s nowhere else to put them so we have to put them here.”

Gede was right. The tiny morgue was already full.

At one end of the corridor, covered by a roof but both its sides open to the air, a team of carpenters was hammering in a flimsy plywood wall. It seemed designed to stop onlookers from wandering in off the street, a job the stunned local police and soldiers weren’t doing. But this is Indonesia and already the shoddy wall was coming apart even as it was being hastily assembled, straining under the weight of hundreds of people – hysterical relatives, media, medicos and rubberneckers – craning for a peek.

Sanglah Hospital, Bali’s main public medical facility, is in Denpasar’s suburbs. The other end of the 25m-long main corridor backs onto a suburban street, blocked off from houses and the street by a 3m concrete wall. Balinese – as many as 200 – had pushed through the outside police perimeter and had now taken up vantage points on the wall separating someone’s house from the clinic.

They could see directly over the makeshift corridor morgue where grief-stricken relatives and friends pulled back charred fragments of Mambo shirts and Quiksilver jackets – more telltale signs of Australianness – to reveal identities that the firestorm might have allowed.

Over by the hospital wall, a foreign girl in her 20s, wearing T-shirt, skirt and thongs, was vomiting into an open drain, comforted by a woman who looked old enough to be her mother, herself sobbing into a tissue. Gede the orderly told me they’d just identified her brother – and perhaps her son – among the dead not 5m away in the corridor. He didn’t exactly know where they were from. “I think Australia,” he said.

There were plenty of Australians inside the un-airconditioned main ward of the hospital; middle Australians, not the $600-a-night Bali spa set but ordinary working people from the big-city outer suburbs and country towns.

The numbers of dead and injured bounced and bandied from bed to bed: 100, 120, 150, as high as 210 dead by some reports. And 300 injured. The word around the hospital was that about half the dead and injured were Australians but, if the patients provided a guide, that percentage seemed more like 80%. There’s an Italian who says six of his friends are missing and a distressed French teenager looking for his girlfriend. Of the 50-odd beds, only four or five are occupied by Balinese. But this was overwhelmingly an Australian ward, an Australian tragedy.

One uninjured man, an Australian in his 50s, had appointed himself ward leader, probably because no one from the overwhelmed hospital seemed to be in charge. Moving from bed to bed, crisis to crisis, he was trying to clear the room of everyone but the few hospital staff, their patients and relatives. A fight broke out between journalists and the man, who was calling the media “vultures”.

As they argued, a photographer was pushed into a bed where a Balinese boy no more than 12 was swathed in bandages, only his face white-red with burns visible through the swabbing. His family suffered the foreigners’ unseemly arguments silently while a young Balinese girl worked the room soliciting foreigners with a donation plate.

Another Australian woman, a volunteer who lives in Bali, opined rather too loudly to a journalist that: “It was OK for the Australians – they’re insured. The Balinese have got nothing.” She, too, copped an earful.

Amid the pandemonium, Val from Perth was bearing up well enough, she said, “considering”. “I’ve got three here in Bali,” Val explained. “I’ve got my son-in-law over there,” she said, pointing to a man burnt, motionless but alive, on a filthy bed. “And my daughter Leanne’s over there. She’s 44. They don’t know what’s wrong with her; they think she’s got a broken arm so we’re making arrangements to airlift her out.

“I think she’ll be all right. I think she’ll make it.” Val herself was shaken, but uninjured. She wasn’t the nightclubbing type and had spent the night in the hotel with her grandson while her kids went out and partied … and almost died.

Across the ward, 21-year-old Steven Betland sat on a bed, his blistered back too painful for him to lie down. His mate Lauren Munroe hovered over him, doing what he could. Steven’s exposed injuries looked shocking, but compared with many of his fellow patients, he seemed all right, well enough to talk about the horror.

A rugby player from Forbes, NSW, Steven said he’d been at the Sari Club for about an hour drinking with mates who were in Bali for a rugby tournament. “People were dancing, having a few beers and then it was just boom,” Steven said.

“The blasts hit, one after another, within seconds of each other,” he said. “First a flash, then another one, two blasts one after another, just a coupla seconds between them,” he said. “We had to climb the wall to get out. The top part, where the roof is, collapsed, then it all started going up in flames, then the wall started caving in.

“And people started scrambling out anywhere and anyway they could.

“There was 25 of us,” Steven explained. “We’re missing three of our mates.”

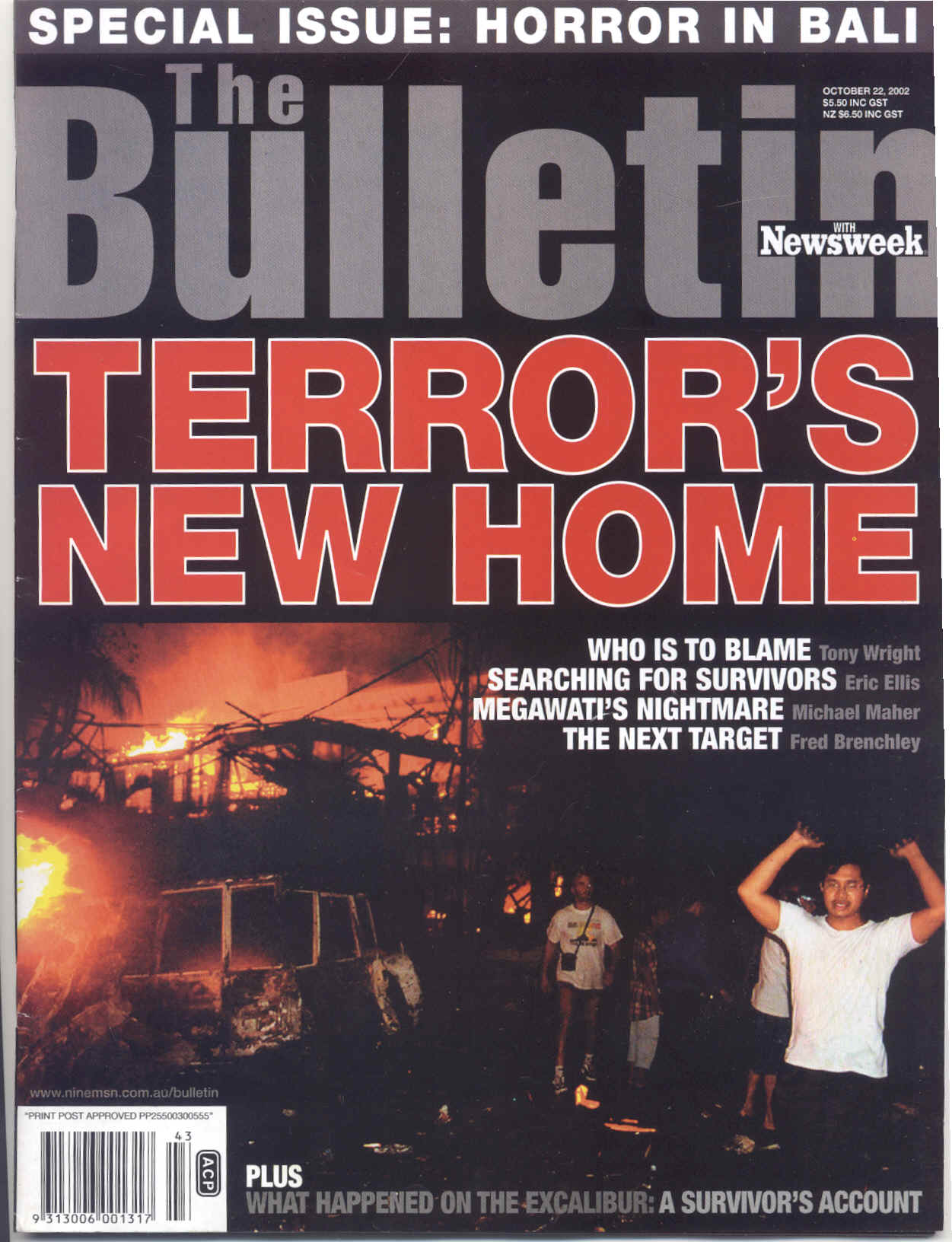

THEY’RE already calling the smouldering remains of the Sari Club on Jalan Legian “Ground Zero”. It’s easy to see why. It’s not anywhere near as big as the New York version but the images are the same: the same vacant space where a building once stood, the same twisted metal, the same contorted pylons, the same pall of tragedy hanging in the air.

And all this in a place that generations of Australians – perhaps two million of us – have escaped to for a good time, our first taste of exotic Asia, a destination so familiar that, for many Australians, Bali seems almost like a seventh state.

It’s a place so thick with Australian youth culture, so pervasive, that revellers in nightclubs such as the Sari Club could stagger home with a skinful of VB after a big Saturday night out singing Cold Chisel’s Khe Sanh and local street urchins would sell the Australian Sunday newspapers, fresh off the Qantas jumbo with Saturday’s footy scores.

Not any more. No one’s going to come back to this dark place for a very long time.

(nominated for Best Story in Magazine Publishers of Australia 2003 awards)